The In-Toto Framework

Securing individual components of a software supply chain—like signing a commit or scanning a docker image—is essential, but it is not sufficient. A sophisticated attacker doesn’t need to compromise the source code or forge the final signature. They can strike in the gaps between steps: tampering with artifacts after they’re built but before they’re tested, modifying binaries between testing and packaging, or substituting images during registry uploads. Traditional security tools validate individual stages but cannot prove that the output of one step became the unmodified input to the next.

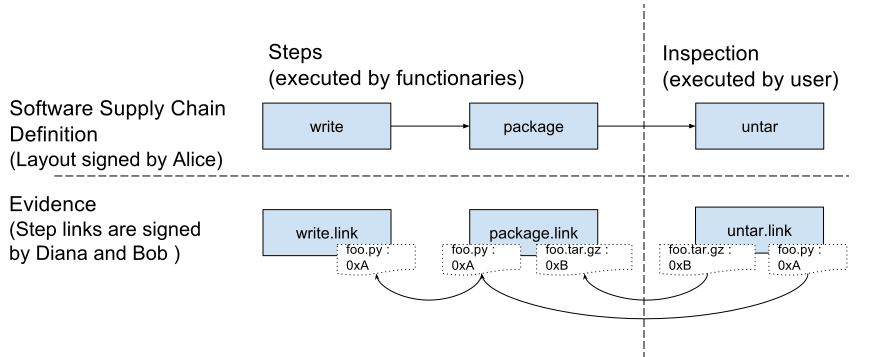

In-toto (Latin for “in whole” or “in total”) is an open-source framework designed to solve this specific problem. It provides a mechanism to verify the integrity of the entire software supply chain, ensuring that not only are the ingredients safe, but the “recipe” was followed exactly as intended.

It allows project owners to define a layout (the rules) for how software should be built, and requires every actor in the chain to provide links (evidence) that they followed those rules. By cryptographically linking each step to the next, in-toto creates an unbreakable chain of custody from source code to production artifact, ensuring that no unauthorized modifications occurred at any transition point.

The Problem: The Chain of Custody

Modern software doesn’t travel in a straight line from developer to user. It passes through multiple stages, each performed by different actors, often on different machines, at different times. A typical enterprise CI/CD pipeline might look like this:

- Developer commits code to Git

- Source Control stores and versions the code

- CI System clones the repository

- Build Agent compiles the source into binaries

- Test Runner executes test suites

- Security Scanner analyzes for vulnerabilities

- Artifact Repository stores the built packages

- CD System retrieves packages for deployment

- Container Registry stores Docker images

- Production Server runs the final artifact

If an attacker compromises the CI Server, they can take the legitimate source code, compile a malicious binary, and pass it to the CD server. The CD server, seeing a binary coming from the trusted CI server, packages and signs it. The final artifact looks legitimate, but it is compromised.

In-toto solves this by requiring a cryptographically verifiable chain of custody. It ensures that step 2 actually used the output from step 1, and step 3 used the output from step 2, without any unauthorized tampering in between.

How In-Toto Solves This

In-toto closes these gaps by creating a cryptographically signed chain of custody. Each step records:

- The exact hash of every input file (Materials)

- The exact hash of every output file (Products)

- Who performed the step (Functionary signature)

- What command was executed

Then, during verification, in-toto ensures:

- The Products of Step 1 exactly match the Materials of Step 2 (same hash)

- The Products of Step 2 exactly match the Materials of Step 3 (same hash)

- And so on, creating an unbroken chain

If an attacker modifies a file between Step 2 and Step 3, the hash mismatch is immediately detected. If a step is skipped, the missing link metadata fails verification. If an unauthorized actor performs a step, the signature validation fails. The result: mathematical proof that the artifact in production is exactly what the developer committed, processed through exactly the expected pipeline, with no unauthorized modifications.

Core Concepts

Understanding in-toto requires distinguishing between what you expect to happen and what actually happened.

1. The Layout (The Expectation)

The Layout is the policy or the “contract” for the supply chain. It is a file (signed by the project owner) that defines:

- Steps: What actions must be performed (e.g., “clone-repo”, “build-binary”, “run-tests”).

- Functionaries: Who is allowed to perform these steps (identified by their public keys).

- Materials and Products:

- Materials: What files go into a step.

- Products: What files come out of a step.

- Inspections: Rules to check that the products of one step match the materials of the next.

Example Layout Logic:

“I expect the user ‘Bob’ to perform the ‘build’ step. He must take the source code files (Materials) and produce a binary file (Product). I expect the ‘test’ step to run on exactly that binary.”

Layout File Structure

A layout file is typically a JSON document that includes:

{

"_type": "layout",

"expires": "2026-12-31T23:59:59Z",

"keys": {

"bob-key-id": { "keytype": "rsa", "keyval": {...} }

},

"steps": [

{

"name": "build",

"expected_materials": [

["MATCH", "src/*", "WITH", "PRODUCTS", "FROM", "clone"]

],

"expected_products": [

["CREATE", "app.bin"]

],

"pubkeys": ["bob-key-id"],

"expected_command": ["make", "build"]

}

],

"inspect": [...]

}The artifact rules use a domain-specific language to express constraints like:

MATCH <pattern> WITH PRODUCTS FROM <step>- Files must match output from previous stepCREATE <pattern>- Files that should be newly createdDELETE <pattern>- Files that may be removedMODIFY <pattern>- Files that may be changedALLOW <pattern>- Files that may exist but aren’t trackedDISALLOW <pattern>- Files that must not exist

2. The Links (The Reality)

As the software moves through the supply chain, every actor (or “Functionary”) creates a Link metadata file. This is an attestation of what they actually did.

When a step is performed, the in-toto client records:

- The exact hash of the files used (Materials).

- The exact hash of the files created (Products).

- The command that was executed.

- The signature of the actor (Functionary) who performed the work.

- The working directory and environment information.

Example Link Logic:

“I am the CI Runner. I ran the command

make build. I started with source filemain.go(Hash: abc…) and I producedapp.bin(Hash: xyz…).”

Link File Structure

{

"_type": "link",

"name": "build",

"materials": {

"src/main.go": {"sha256": "abc123..."},

"Makefile": {"sha256": "def456..."}

},

"products": {

"app.bin": {"sha256": "xyz789..."}

},

"byproducts": {

"stdout": "...",

"stderr": "...",

"return-value": 0

},

"command": ["make", "build"],

"environment": {...}

}How Verification Works

The power of in-toto lies in the final verification phase. When a user wants to install the software (or an admission controller like DevGuard inspects it), they run the in-toto verification.

The verifier takes the Layout (the rules) and collects all the Links (the evidence). It then overlays them to check for discrepancies.

The verification workflow: The Layout defines the expected steps, and the Links provide the evidence. The Verifier ensures they match.

The in-toto verification process follows these steps:

- Load and Validate Layout: Verify the layout signature and check expiration date

- Collect Link Metadata: Gather all link files from functionaries

- Verify Signatures: Ensure each link is signed by an authorized functionary

- Check Step Sequence: Verify all required steps were executed

- Validate Artifact Flow: Ensure materials and products match across steps

- Run Inspections: Execute final verification rules

- Check Artifact Rules: Validate all CREATE, DELETE, MODIFY, MATCH constraints

The verification fails if:

- Unauthorized Actor: A step was signed by a key not listed in the Layout.

- Tampering: The hash of a “Product” from Step A does not match the hash of the “Material” in Step B. (This indicates the file was modified in transit).

- Missing Step: A required step in the Layout has no corresponding Link metadata.

- Command Mismatch: The command executed differs from the allowed command in the Layout.

- Artifact Rule Violation: Files were created, deleted, or modified in ways not permitted by the layout.

- Expired Layout: The layout has passed its expiration date.

- Failed Inspection: A post-build inspection rule was violated.

Trust Model

In-toto operates on a threshold signature model. The layout can require that multiple functionaries sign off on a single step, preventing any single compromised key from undermining the entire supply chain.

For example, you could require that both the CI system and a security scanning service sign the “build” step, ensuring two independent verifications occurred.

In-Toto and SLSA

You will often see in-toto mentioned alongside SLSA (Supply-chain Levels for Software Artifacts). It is important to understand their relationship:

- SLSA is a standard that defines security levels (Level 1, 2, 3, 4) and requirements for build security.

- In-toto Attestation Framework provides the format that SLSA uses to express provenance metadata.

- In-toto Framework (layouts and links) is a separate, complementary verification system.

SLSA Uses In-Toto Attestations

SLSA recommends using the in-toto attestation format to store provenance data. When you generate a “SLSA Provenance” document, it is structured as an in-toto attestation with a SLSA-specific predicate:

{

"_type": "https://in-toto.io/Statement/v0.1",

"subject": [{"name": "app.bin", "digest": {"sha256": "..."}}],

"predicateType": "https://slsa.dev/provenance/v1",

"predicate": {

"buildDefinition": {...},

"runDetails": {...}

}

}The key distinction:

- In-toto attestations are a general-purpose format for signing metadata about artifacts

- SLSA Provenance is a specific type of attestation (a “predicate type”) focused on build provenance

- In-toto layouts/links are a separate workflow verification system that can use attestations

In-Toto Attestation Framework

The in-toto team developed a general-purpose Attestation Framework that extends beyond supply chain metadata. An attestation is a signed statement about a software artifact, consisting of:

- Envelope (DSSE): Provides cryptographic signatures

- Statement: Contains subject (the artifact) and predicate type

- Predicate: The actual metadata payload

This format is now used for multiple predicate types:

- SLSA Provenance (build metadata) -

https://slsa.dev/provenance/v1 - SPDX (SBOM) -

https://spdx.dev/Document - CycloneDX (SBOM) -

https://cyclonedx.org/bom - Vulnerability Scans -

https://in-toto.io/attestation/vuln/v0.1 - Test Results -

https://in-toto.io/attestation/test-result/v0.1 - SCAI (Supply Chain Attribute Integrity)

Combining In-Toto Framework with SLSA

While SLSA uses in-toto attestations for provenance, you can also use the full in-toto framework (with layouts and links) alongside SLSA:

- Generate SLSA Provenance attestations during your build

- Create in-toto links for other supply chain steps (testing, scanning, deployment)

- Define an in-toto layout that specifies which attestations are required

- Use in-toto verification to ensure all steps were completed correctly

This combination provides both:

- SLSA compliance for your build provenance

- End-to-end verification of your entire supply chain with in-toto

Read more about this relationship in the SLSA Framework chapter and the official SLSA/in-toto blog post.

Limitations and Considerations

While in-toto provides strong guarantees, it’s important to understand its boundaries:

- Trust Anchors: The security depends on the integrity of the layout file and the project owner’s key. These must be protected rigorously.

- Functionary Key Management: If a functionary’s private key is compromised, an attacker can create valid-looking link metadata.

- Side Channels: In-toto doesn’t prevent timing attacks, resource exhaustion, or other side-channel attacks during the build process.

- Operational Overhead: Implementing in-toto requires process changes and adds complexity to your CI/CD pipeline.

Simplifying In-Toto with DevGuard

In-Toto is great but complex. It is necessary to think about the root layout, generate those link files, store them somewhere, download them somewhere else, gather all public keys, and verify the link files against the layout. These requirements introduce friction that may deter adoption.

DevGuard addresses these challenges by streamlining the integration and providing developers with a seamless way to benefit from In-Toto’s robust security features. Key improvements include:

Automated Root Layout Management

DevGuard provides the root.layout file automatically, defining the supply chain steps, materials, products, and rules. This eliminates the need for manual layout creation and ensures consistency across the supply chain.

Simplified Key Management

DevGuard manages public and private keys transparently for users. Developers generate access tokens, which are private and public keypairs. Those tokens can be used for authentication and signing. Private keys always remain local, while public keys are securely stored in DevGuard for verification purposes.

Integrated Link File Generation and Storage

DevGuard automatically generates and signs link files inside the reusable workflow definitions and CI/CD-GitLab-Components for each step in the supply chain. These files are securely transmitted to and stored within DevGuard, eliminating the need for manual handling.

Continuous Verification

Whenever DevGuard receives the last link file of the supply chain, it automatically verifies the entire chain against the root layout. DevGuard provides a simple HTTP-Endpoint to get the state of the chain. This simplifies the verification process inside a production environment by magnitudes.

GET /api/v1/verify-supply-chain?supplyChainId=XYZ&supplyChainOutputDigest=ab23cdThe call to this endpoint results either in a 200 OK or a 400 Bad Request response.

Besides that, the verification can be done manually by downloading the links and verifying them against the root.layout. All those artifacts are stored and free to download by the developer.

Conclusion

The in-toto framework shifts security from trusting the person to trusting the process. By cryptographically chaining every step of the software delivery pipeline—from the developer’s laptop to the final production server—it eliminates the “black box” of software building.

It provides the mathematical proof that the software running in production is exactly what the developers intended, with no unauthorized modifications along the way.

Unlike traditional code signing (which only validates “who”), in-toto validates “who did what, when, and how”—creating an auditable trail for the entire software supply chain.