What is Supply Chain Security?

In modern software development, you rarely write 100% of your own code. Instead, you assemble products using a vast ecosystem of third-party libraries, build tools, container images, and CI/CD pipelines.

In fact, it has been estimated that 70-90% of current software is composed of

Free and Open Source Software (FOSS). This heavy reliance on external dependencies has fundamentally altered the threat landscape,

shifting the risk from the code you write to the components you consume and the tools you use to deploy them.

Supply chain security is the practice of ensuring that every component, process, and actor involved in the creation and delivery of your software is verified, untampered, and trustworthy.

Effective supply chain security requires a comprehensive understanding of your software’s origins.

What is the Software Supply Chain?

A software supply chain consists of all the steps and components involved in creating, building, and deploying software in the Software Development Life Cycle. It includes the tools, processes, and people responsible for writing and transforming source code into a deployable application.

The software supply chain for a typical project could involve for example (not exhaustive):

- A developer writing source code

- Version control systems (Git, SVN, etc.)

- Third-party software libraries

- Build tools (Maven, make, etc.)

- CI/CD software (Jenkins, GitHub Actions, etc.)

- Deployment system packaging the executable into a Docker image

- Container registry storing the Docker image for deployment

- Production environment running the Docker image

- Package management software and ecosystems (npm, pip, etc.)

- …

Every one of these components has to be secured. A single vulnerability can put the entire software supply chain at risk, which is why each stage needs to be addressed.

The Threat Landscape

Understanding the potential threats to the software supply chain is crucial to ensure its security.

By mapping the software supply chain, we can pinpoint vulnerabilities throughout the development lifecycle.

These risks are categorized into four strategic domains:

Source,

Build,

Dependency,

and Deployment & Runtime threats.

1. Source Threats

Source threats target the earliest stage of development—the code itself and the systems that manage it. Attackers aim to compromise source code repositories to inject malicious code or steal intellectual property before the build process even begins.

Examples of Source Threats

- Unauthorized Code Changes: An attacker gains access to a developer’s account or maintainer rights for a public repository and silently commits a backdoor into the codebase.

- Repo Configuration Weaknesses: A public GitHub repository is accidentally configured to allow anyone to push code, or branch protection rules are bypassed.

- Insufficient Code Review: Malicious or vulnerable code is merged into the main branch because peer review processes were skipped or automated scanners were ignored.

The XZ Utils logo contributed by the attacker Jia Tan during their time of gaining trust with the maintainers of the repository.

Real-World Example: The 2024 XZ Utils Backdoor In this sophisticated social engineering attack, a malicious actor known as “Jia Tan” spent years building trust to gain maintainer rights over XZ Utils, a widely used compression library. Once in control, they injected a backdoor designed to allow unauthorized remote code execution on Linux servers.

Impact: The attack was discovered by chance just weeks before it would have merged into stable Linux distributions. This near-miss highlights the importance of supply chain security vigilance. While this miracle discovery prevented the infection of hundreds of millions of servers globally, the compromised versions (5.6.0 and 5.6.1) still reached users of rolling-release distributions like Fedora Rawhide, Kali Linux, and openSUSE Tumbleweed.

2. Build Threats

Build threats are a major focus of supply chain security. These threats target the “factory” where code is turned into executable software. If the build environment or the process is compromised, the resulting artifact will be malicious, even if the original source code was clean.

Examples of Build Threats

- Compromised Build Server: An attacker infects the CI/CD pipeline (e.g., Jenkins or GitHub Actions), causing it to inject malware during the compilation process.

- Environmental Drift: The build environment uses outdated or unpatched tools that have known vulnerabilities, which attackers exploit to alter the build output.

- Artifact Tampering: A legitimate binary is replaced with a malicious version immediately after the build is completed but before it is signed or stored.

Real-World Example: SolarWinds Incident (2020) This incident illustrates a critical failure in supply chain security. Attackers compromised the build environment and continuous integration server, allowing them to modify and infect software updates for the Orion network monitoring tool.

Impact: The fallout was severe, reaching over a dozen U.S. government departments—including the military, executive branch, and intelligence services—who unknowingly installed the compromised updates.

3. Dependency Threats

Dependency threats represent one of the most common supply chain security challenges. Modern software relies heavily on third-party libraries and open-source packages. These threats exploit this trust by introducing vulnerabilities through the external components your software consumes.

Examples of Dependency Threats

- Typosquatting: An attacker publishes a malicious package with a name very similar to a popular library (e.g.,

react-domvs.reac-dom), hoping developers install the wrong one by mistake. - Dependency Confusion: An attacker uploads a malicious package to a public registry with the same name as an internal, private package, tricking the build system into pulling the public (malicious) version.

- Vulnerable Transitive Dependencies: A library you use depends on another library that has a critical vulnerability (like Log4j), compromising your application indirectly.

Real-World Example: Log4Shell (2021) The Log4Shell vulnerability demonstrates the massive reach of dependency threats and the importance of supply chain security. A critical flaw in how the ubiquitous Java logging library Log4j processed log messages allowed attackers to execute arbitrary code remotely (RCE) simply by sending a specific text string to a vulnerable server.

Impact: Because Log4j was embedded as a dependency in millions of applications—from iCloud and Steam to enterprise software—the vulnerability left a vast portion of the internet exposed. It forced organizations globally to pause development and scramble to patch deep chains of transitive dependencies.

4. Deployment and Runtime Threats

Deployment and runtime threats extend supply chain security concerns beyond the build process. These threats occur after the software has been built and is running in its destination environment. Attackers target the deployment infrastructure or the application while it is active to manipulate its behavior or steal data.

Examples of Deployment Threats

- Insecure Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC): Deployment scripts (e.g., Terraform or Kubernetes manifests) are misconfigured, leaving cloud buckets or API endpoints exposed to the public.

- Runtime Injection: An application running in production is exploited via a vulnerability (like SQL Injection or Remote Code Execution) to execute malicious commands.

- Unverified Artifact Deployment: The production environment accepts and runs a container image that hasn’t been signed or verified, allowing an attacker to deploy a rogue version of the application.

Real-World Example: The Equifax Data Breach (2017) While often cited as a failure to patch, this incident fundamentally illustrates a Runtime Injection attack via a supply chain dependency. Equifax was running a version of the Apache Struts framework with a known flaw (CVE-2017-5638) in how it parsed HTTP headers.

Attackers exploited this by sending web requests with malicious commands injected into the Content-Type header. The running application parsed the header and immediately executed the code within it,

allowing attackers to bypass authentication entirely.

Impact: The breach resulted in the theft of 147.9 million American consumer records. It also exposed data for 15.2 million UK citizens and compromised approximately 10–11 million drivers’ licenses, highlighting how a single runtime vulnerability can lead to catastrophic data loss and why comprehensive supply chain security is critical.

Core Mitigation Principles of Supply Chain Security

To counter the threats described in the previous section, supply chain security relies on four fundamental concepts best implemented in your CI/CD (Continuous Integration/Continuous Deployment) pipeline. While traditional application security focuses on finding vulnerabilities in your own code, supply chain security focuses on verifying the trust and transparency of everything that enters and exits your pipeline. These supply chain security principles form the foundation of a robust defense strategy.

Visibility

Visibility is the first pillar of supply chain security. You cannot secure what you cannot see. Modern software is rarely written from scratch; it is assembled from hundreds or thousands of open-source libraries and third-party components.

Visibility is achieved through a Software Bill of Materials (SBOM). An SBOM is a formal, machine-readable inventory of every dependency, library, and module included in your software. Just as a list of ingredients on a food package allows consumers to avoid allergens, an SBOM allows security teams to rapidly identify if they are affected when a major vulnerability is discovered in a widely used component. SBOMs are essential for effective supply chain security.

For example, during the CI build process, a scanner analyzes the project’s manifest files (like package.json) and generates an SBOM JSON file, which can then get automatically checked for compromised packages regularly.

Identity and Integrity

Identity and integrity are core components of supply chain security. In a distributed supply chain, it is difficult to know if a piece of code is authentic. Attackers may impersonate a trusted maintainer or inject malicious code into a package during transit.

-

Identity verifies who created an artifact (a developer or a build system).

-

Integrity verifies that the artifact has not been altered since it was created.

This is solved through Cryptographic Signing. By applying a digital signature to code commits, container images, and binaries using a private key, organizations ensure that the software received at the end of the chain is exactly identical to the software that was produced at the start.

For example, a developer signs their commit with their private GPG key, proving they wrote the code. Later, the CD system signs the final container image before pushing it to the registry. When a server pulls that image to run it, it checks the signature against a public key. If the signature is invalid, indicating the file was tampered with, the server refuses to run it.

Provenance

Provenance is a critical aspect of supply chain security. While signing proves who signed an artifact, it does not prove how it was built. A signed binary could still be malicious if it was built on a compromised laptop or build server.

Provenance is the verifiable “chain of custody” for software. It is a set of authenticated metadata, often called Attestations that records exactly how a software artifact was produced. Provenance strengthens supply chain security by providing transparency into the build process. This includes which source code commit was used, which build parameters were set, and which specific build environment or CI runner performed the compilation. Provenance allows systems to verify that the software was built in a trusted, isolated environment rather than an insecure one.

The in-toto specification is the industry standard for this attestation data. During a build, the CI system observes the process and creates an in-toto attestation that certifies: “I, the Build Service, built this artifact using source commit X on runner Y at time Z.” This distinguishes an official, secure build from a counterfeit one built on an attacker’s machine.

Policy Enforcement

Policy enforcement completes the supply chain security framework. Visibility, integrity, and provenance provide data, but that data must be acted upon. Policy enforcement is the automated governance layer that sits between the build and the deployment.

Instead of relying on manual security reviews, policy engines use the data from the previous three pillars to make automated decisions, blocking insecure artifacts from moving downstream. A policy might state: “Do not allow this container to run in production unless it has a valid SBOM, is signed by our trusted key, and has provenance showing it was built on our secure server.” This ensures that supply chain security standards are applied consistently across the entire organization.

For instance, a Kubernetes Admission Controller acts as a final gatekeeper. It is configured with a policy that states: “Reject any deployment that does not have a valid SBOM and a signature from our CI system.” Even if a developer accidentally tries to deploy an insecure image, the cluster automatically rejects it.

Industry Frameworks and Standards

To standardize the supply chain security practices described above, the industry relies on two primary frameworks:

NIST SSDF and SLSA.

While they share the same goal of improving supply chain security, they approach the problem from different perspectives: SSDF focuses on the process, while SLSA focuses on the artifact.

NIST SSDF (The Process Standard)

The Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF), published by NIST (SP 800-218), outlines high-level practices for the entire software lifecycle. It is less about specific tools and more about organizational culture and policy.

The framework requires organizations to:

-

Establish Policy: Create formal policies for secure development, which are often required for compliance (e.g., ISO 27001, SOC 2).

-

Secure the Environment: Protect source code repositories (e.g., via commit signing) and restrict access to authorized developers only.

-

Monitor Dependencies: verify that third-party components meet security requirements.

-

Automate: Implement continuous vulnerability scanning and adopt DevSecOps practices.

In short, SSDF mandates that an organization has a secure process and a trained team to run it.

SLSA (The Artifact Standard)

Supply-chain Levels for Software Artifacts (SLSA) is a supply chain security framework specifically designed to guarantee the integrity of the final software output.

Its fundamental concept is Provenance: metadata that describes exactly how an artifact was created, including the source code version, the build platform, and external parameters used. SLSA relies on the in-toto framework to provide the standard format for this metadata.

SLSA defines four maturity levels to guide organizations from basic documentation to advanced hardening:

-

Level 0: No security guarantees or specific measures.

-

Level 1: Provenance exists. Metadata is available to trace how the software was built, allowing for better analysis.

-

Level 2: Signed Provenance. The build runs on a hosted platform (not a developer’s laptop) and generates signed provenance to prevent basic tampering.

-

Level 3: Hardened Builds. The build process is isolated and resistant to tampering, even from insiders, offering the highest level of protection.

The “Shift Left” Philosophy

Implementing supply chain security is not just about adding new tools; it requires a fundamental shift in when security checks occur. This concept is widely known in the industry as “Shift Left”.

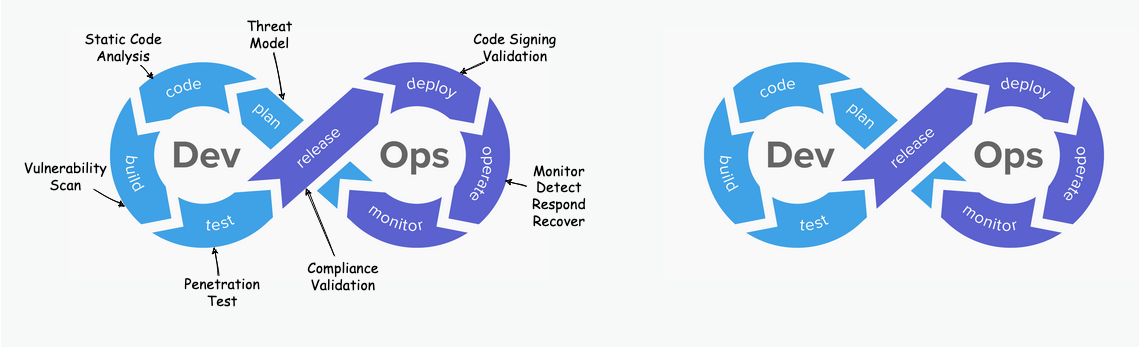

The “DevSecOps 8” showing the individual steps of devolopment and operations. Right the traditional DevOps pipeline, left the DevSecOps pipeline with security measures at every step.

In a traditional software lifecycle, modeled left-to-right from Design to Production, or as is more common in the industy with the “DevOps 8” as shown above, security testing often happened at the very end—just before deployment. If a vulnerability was found, the release was blocked, and developers had to scramble to fix code they wrote weeks ago.

Shift Left moves security processes to the earliest possible point in the development timeline:

-

Design Phase: Choosing safe dependencies before writing code.

-

Coding Phase: IDE plugins warn developers about vulnerable packages in real-time.

-

Build Phase: Automated CI pipelines generate SBOMs and sign artifacts immediately upon commit.

Why it matters

The cost of fixing a security defect increases exponentially the further “right” it moves in the lifecycle. Replacing a compromised library while writing code takes minutes. Replacing that same library after it has been deployed to thousands of production servers takes days or weeks and introduces significant risk.

By shifting left, supply chain security becomes an integrated part of the developer workflow, rather than a final gatekeeper.

Conclusion

Supply chain security is no longer optional in an era of automated, multi-layered software delivery. Implementing supply chain security requires moving beyond simple vulnerability scanning and into the realm of provenance and integrity. By understanding the flow of code from source to production, and by demanding cryptographic proof of every transformation, organizations can significantly reduce the risk of sophisticated supply chain attacks. Investing in supply chain security today protects your organization from tomorrow’s threats.

In the following sections, we will explore the specific frameworks DevGuard uses to implement these concepts and frameworks, including In-toto and SLSA.

References

- OWASP Software Supply Chain Security Cheat Sheet

- SLSA Threats Overview (v1.0)

- Warum Sicherheit in der Software-Lieferkette 2024 unverzichtbar ist